By Harry Minium

It was 1959, before Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. became a national figure. But as NAACP officials prepared 17 students to become the first Black children to attend previously all-white schools in Norfolk, they preached King's message of nonviolent resistance.

Patricia Turner, who has two degrees from Old Dominion University and is one of the Norfolk 17, as those brave pathfinders are known, recalls the lessons well.

"We were told to hold our heads up and walk beside a wall," she said.

"Never sit in the back of the classroom. Don't use the restroom. Never drink from the water fountain.

"If someone hits you, keep your head up and keep walking. If someone knocks your books out of your hands, pick them up and keep going.

"If someone spits in your face, remember, it's just water."

She suffered all those indignities when she attended Norview High School. When asked to name her worst memory, she said it was the time "a young woman spit in my face. I wasn't expecting it. I wasn't looking."

You can still hear the pain in her voice.

More than six decades after the Norfolk 17 bravely walked into six schools, their story remains little known, as does that of Virginia's Massive Resistance, when Virginia chose in 1958 to close its schools rather than integrate. It took a federal court order to force the schools to reopen in February 1959 and allow the 17 African American students to attend previously all-white schools.

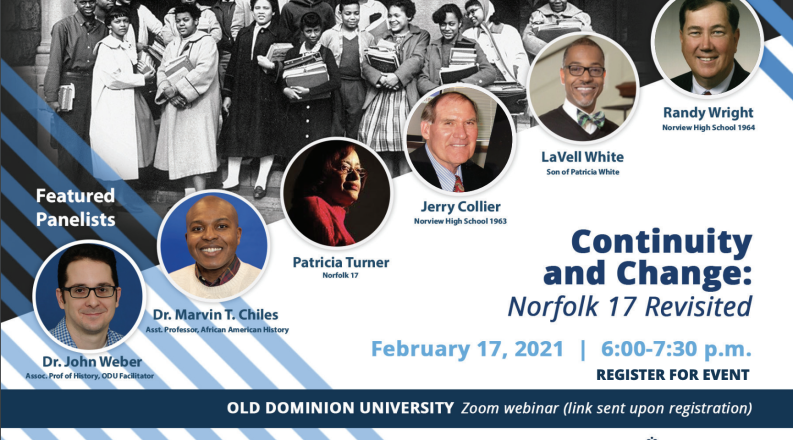

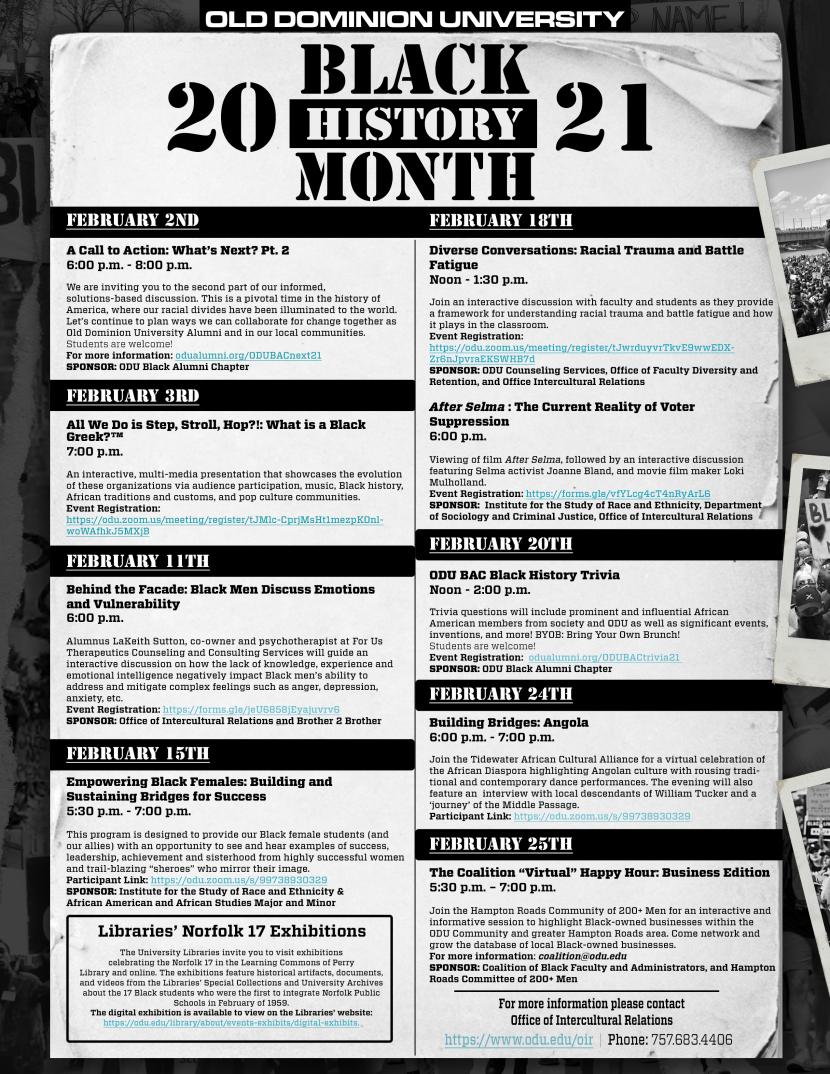

As part of the effort to educate the public about their story, ODU's Darden College of Education and Professional Studies is hosting "Change: Norfolk 17 Revisited," a 90-minute virtual panel discussion that is free and open to the public, at 6 p.m. Feb. 17. To register, click here.

Turner will be joined on the panel by Jerry Collier, president of the Norview High School class of 1963 and a classmate of Turner; LaVell White, son of Patricia White, one of the Norfolk 17; former Norfolk City Councilman W. Randy Wright, a classmate of and close friend of James "Skip" Turner, Turner's deceased brother; and two ODU faculty members - Martin T. Chiles, an assistant professor of African American history, and John Weber, an associate professor of history who will facilitate the discussion.

The panel discussion was in part inspired by the research of Yonghee Suh, associate professor of social studies and history education at ODU. Suh has been the co-host for the past two Landmarks of American History and Culture Workshops for School Teachers, focusing on the history of school desegregation in Virginia.

These workshops have been funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities, and she will host another this summer. Because of the pandemic, this year's workshop will be held virtually.

The Supreme Court unanimously ruled that segregated schools were unconstitutional in 1954 in Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka. Virginia's decision to close schools in half a dozen cities and counties, including Norfolk, was popular across much of the state.

Few from outside the state who attend her seminars have heard of Massive Resistance, Suh said.

"When people think of Virginia, they think it is genteel," she said. "They don't realize just how powerful the resistance to integration was in Virginia or how long it lasted. "I felt like we really need to honor to the Norfolk 17 and their experience and let people know how painful but yet how powerful their message is."

Both Andy Heidelberg, a deceased member of the Norfolk 17, and Turner wrote books about their experiences at Norview High. Turner's was written for children and Heidelberg's for adults. He describes people swearing, spitting and throwing rocks the first day he entered Norview.

Turner said once schools were finally integrated, the story of the Norfolk 17 was ignored.

"People don't know how bad things were for us or what we did," she said. "Virginia stuffed us under the rug and stomped on us for so long that we felt like we didn't even exist. They don't teach much about Massive Resistance in the schools. It's only a hiccup in the history books. And they don't talk about us.

"I don't understand how you can teach Massive Resistance without telling the truth about the massive resisters."

Nine of the 17 are still living, Turner said.

Turner said white kids at the time had been "brainwashed" to think Blacks were inferior. But as time went on, and students began to see how well the Norfolk 17 did academically, that began to break down barriers. One classmate told her parents that Turner was smarter than her in math class and that she wanted Turner to help her study.

Turner said the Norfolk 17 were the "cream of the crop." Hundreds of students took tests to qualify to go to white schools.

"Eventually, a lot of our classmates realized what their parents told them wasn't true," she said.

Because crosses were being burned in front of some homes of the Norfolk 17, Turner said Black kids also shunned them. Their parents didn't want their kids getting involved.

"We gave up our youth," Turner said. "We didn't go play. We had to study. We had to make sure that our grades were on track.

"It hurt that we were shunned by our own. That's one of the reasons we became so close. We felt like we were all alone."

She said the physical violence was difficult to endure, "but it's not the sticks and stones that hurt. It was the words I heard. They hurt for a long time."

Over time, many of those who physically and verbally abused her, including a man who later became a judge, apologized. So did that girl who spit in her face.

"I just gave her a big hug and I forgave her," said Turner, who says she hasn't told anybody the name of the woman, who died a few years ago. "I saw her several times over the years and every time I did, she would cry on my shoulder."

Turner has a master's degree and doctorate from ODU and says she's proud that her alma mater is doing so much to honor the Norfolk 17. Last month, she accepted the Hugo Owens Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Award on behalf of the Norfolk 17.

She credits President John R. Broderick for making ODU a more diverse institution and reaching out to the Black community.

"President Broderick made the effort to find out who I am and reach out to me," she said. "How many university presidents can you say that about?

"ODU is doing a lot to recognize us. And we appreciate that."