By Harry Minium

Sonny Allen, who won Old Dominion University's first national championship, built the foundation for ODU's successful Division I basketball debut and integrated Virginia college basketball, passed away peacefully Sept. 11 in Reno, Nev.

Allen, 84, had suffered for years from Parkinson's Disease, and his son, Billy Allen, said the disease had worsened in recent months. Allen's wife, Donna, and four children, including daughters Jackie Eldrenkamp, Kelly Marcantel and Jennifer Allen, were in Reno when he passed, as were stepchildren Jimmy Warner and Tedi Holdmann.

Allen is also survived by eight grandchildren and five great grandsons.

"He fought a good fight and was an awesome dad for all of us," Billy Allen said. "He's in heaven now. There's no more Parkinson's, no more suffering.

"Dad knew this was coming. He knew the end was near. We had great talks about this, and he was strong and faithful. He knew where he was going and that's a much better place than he was here."

Allen was one of the giants in ODU athletics even though he was here just 10 years. He came to ODU in 1965, a time when the Monarchs played on what is now essentially the Division III level at high school gyms, and built a powerhouse Division II program that at times sold out Norfolk's Scope arena.

The Monarchs advanced to the 1971 Division II national title game, losing to Evansville in Evansville, Ind., and then won the 1975 championship, beating the University of New Orleans in Evansville.

Allen won 181 games at ODU.

But his most important contribution at ODU may have been the cause of social justice. Virginia was segregated, as was state college basketball. When he was being interviewed for the ODU job, Allen asked then Athletic Director Bud Metheny if he could recruit African American players, and Metheny said yes.

"If Bud had said no, I wouldn't have taken the job," Allen later said.

He recruited Arthur "Buttons" Speakes, an African American guard from Huntington, W.Va., whom Allen scouted while coaching at Marshall, his alma mater.

Speakes could only play in freshman games his first season at ODU and before one game at Hampden-Sydney, had to sleep in the gym because hotels there were segregated. Opposing fans often razzed him and shouted racial epitaphs.

Allen added Bob Pritchett, a black junior college All-American to his roster during the offseason, and Pritchett and Speakes played their first varsity season at ODU in 1966-67. Both suffered indignities, but Allen's decision opened the door for other predominantly white schools to recruit Black players.

"He was ahead of his time, certainly before the word was coined, at being inclusive," ODU Athletic Director Wood Selig said. "It speaks to his character that no matter what public opinion or prevailing thought would be, he did the right thing."

Speakes said he was devastated to hear of Allen's passing.

"He meant the world to me because he gave me a chance," he said. "I wasn't going anywhere fast in Huntington. He gave me a chance to play ball and get my education.

"He kind of looked after me because I was going into strange territory as the first Black player at a predominantly white school in Virginia.

"He promised my mother that he'd look out for me and he did. He was courageous. We went to some places, we played some games, where he had to hold his breath. But we did all right."

Allen left ODU for SMU after winning the national championship and by then, ODU had a solid fan base that generally filled up the 4,800-seat ODU fieldhouse. Moreover, he left the bulk of his team, including stars Wilson Washington, Joey Caruthers and Jeff Fuhrmann.

They helped take the Monarchs back to the Division II Final Four in 1977. A year later, coach Paul Webb led ODU into Division I and the Monarchs went 25-4, upset Virginia and Georgetown and advanced to the NIT.

Washington, a Norfolk native and transfer from Maryland, was the star of that team.

Allen was a quiet and humble man and his family says that comes from his upbringing in Moundsville, W.Va., where he was raised in poverty.

Allen was 3 when his father left his mom, and she struggled while raising five children on her own. His childhood poverty instilled in him an intense determination to succeed.

He worked at a steel mill for a year after graduating from high school to save money for college, and then enrolled at Marshall, where he walked-on and became a star. He roomed with future NBA star Hal Greer, an African-American.

Allen coached Marshall's freshman team before coming to ODU.

He coached at SMU, Nevada in the World Basketball League, the Continental Basketball League and the WNBA, where he coached former ODU star Ticha Penicheiro.

Allen retired in 2001 with a 613-383 career record.

Not only did he consistently win, he changed the game. While at ODU, he wrote a book about fast-break basketball in which, for the first time, players were numbered - No. 1 was the point guard, No. 2 the shooting guard, etc. His high-scoring fast-break offense ended up being copied by dozens of coaches.

In his 10 years at ODU, the Monarchs averaged 85 or more points nine times, including 98.2 points in 1967-68.

Allen was praised as one of the great offensive minds in college basketball by former coaches such as Bobby Knight from Indiana, George Raveling from USC and Paul Westhead, who copied the ODU fast-break at Loyola Marymount and set national scoring records.

Selig grew up in Larchmont in Norfolk, just steps away from the Allen family, when Sonny coached at ODU and became best friends with Billy Allen. They played basketball together at Norfolk Collegiate.

"Not many others have had the influence on Old Dominion University, and by that, I don't just mean the basketball program, that Sonny Allen had," ODU Selig said.

"He was always pushing the envelope, whether it was integrating college basketball in Virginia or revolutionizing the game.

"I saw him coach so many games at Old Dominion, so I appreciate not only what he meant to ODU basketball, but to the game itself."

Former ODU All-American Dave Twardzik, whose only scholarship offer came Allen, went on to star for the Virginia Squires of the ABA and the NBA's Portland Trail Blazers, where he won an NBA championship. He is ODU's radio color commentator and works for the San Antonio Spurs.

"He was the foundation of Old Dominion basketball," Twardzik said. "What he did to this program in just 10 years is amazing.

"Sonny wore many hats in my life. He was my coach, kind of a surrogate father figure, then became a friend and we worked together a couple of times."

Allen wasn't as well-known as coaches with fewer accomplishments, and Twardzik said that's because he was not a self-promoter.

"He was a man who let his actions speak louder than his words," Twardzik said. "He was a man of silent dignity.

"Unlike a lot of coaches, I never heard Sonny singing his own praises. I would hate to think of where I would be without Sonny Allen in my life."

ODU coach Jeff Jones said Allen's death "was very sad news. Sonny was a true innovator, a very underrated coach, but most of all he was a wonderful human being.

"Our thoughts and prayers are with his family today."

Webb also paid homage to Allen.

"Sonny was an outstanding basketball coach who had great success everywhere he coached," he said.

"We had just talked recently. He was a dear friend and I'm so sorry to hear about his passing."

Allen's daughter, Jackie Eldrenkamp, said the family is doing well under the circumstances.

"We go back and forth between crying and laughing, because we're telling stories about great times and what a great dad he was," she said. "He wasn't just a great basketball coach and a great person. He was a great father.

Billy Allen said his father insisted that there be no funeral.

"That was dad," Allen said. "He was so humble. He said, 'no funeral, no fuss.'"

"We will get together at some point and celebrate his life, hopefully with family and friends. We'll get together and tell stories about dad. There were so many great stories to tell."

Related News Stories

ODU’s Men’s Basketball Coach Is Winning His Fight with Prostate Cancer

Jeff Jones’ PSA tests indicate the disease has been dormant for nearly two years. (More)

ODU’s Esports Team Will Begin Competition This Month

The University will be home to the only varsity Esports program at a public four-year school in Virginia. (More)

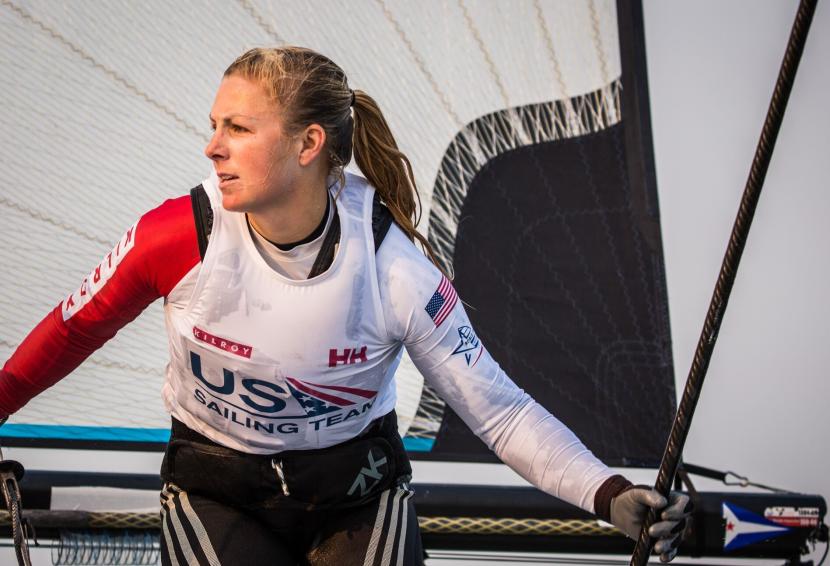

ODU Alum Will Chase an Olympic Medal a Year Later Than Planned

Stephanie Roble ’11 is set to compete in the sailing competition in Tokyo. (More)