Introduction

The Social Science Research Center (SSRC) at Old Dominion University recently completed data collection for the 13thannual Life in Hampton Roads (LIHR) survey. The purpose of the survey is to gain insight into residents’ perceptions of the quality of life in Hampton Roads as well as other topics of local interest such as perceptions of police, politics, the economy, education, health and COVID, transportation and other issues. A total of 639 telephone surveys were completed between May 31 and Aug. 19, 2022.

Surveys this year were all completed over the telephone, as was the case prior to 2020. In 2020, due to COVID-19, surveyswere completed via online web panels. In 2021, a mixture of online web panels and telephone surveys were used. This year, a mixture of listed and random-digit dial (RDD) cellphone and landline telephone numbers were used. From 2012 to 2019, RDD landline and cell phone samples were used. This change limits to some degree the ability to compare this year’s results with those from previous years or to confidently generalize the results to the Hampton Roads population as a whole.

However, as with previous years, this year’s survey data was weighted to match city population distributions on severalvariables including race, Hispanic ethnicity, age and gender, along with access to broadband internet service. For more detailed information on the methodological changes and potential impacts please see the Methodology section in the full report, or please contact the SSRC directly.

Negative Experiences with the Police

For the past few years, the Life in Hampton Roads survey has included two items measuring negative experiences with the police:

- In the past year, have you or someone close to you had a negative experience with police (e.g., the officer shouted at you, cursed at you, pushed or grabbed you)?

- In the past year, have you heard of someone in your local community who had a negative experience with police (e.g., the officer shouted at them, cursed at them, pushed or grabbed them)?

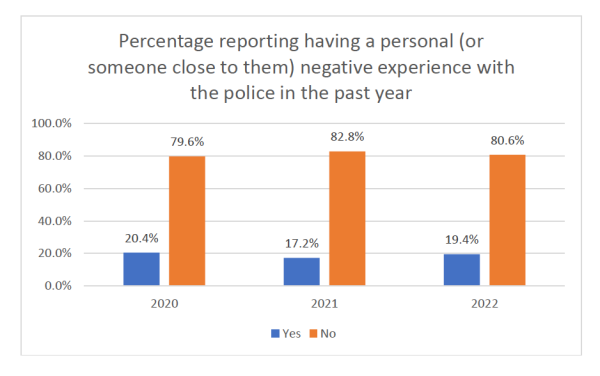

We note that both items refer to relatively serious negative experiences and are not issues related to standard daily encounters with the police (e.g., a brief conversation about directions or a traffic stop). Response categories were simply “yes” and “no.” This year about 19% of the respondents reported that they (or someone close to them) had had a negative experience with the police, up slightly from 17% reported last year and down one percentage point from the year before. All in all, these minor differences are not statistically different and are likely due to sampling variation.

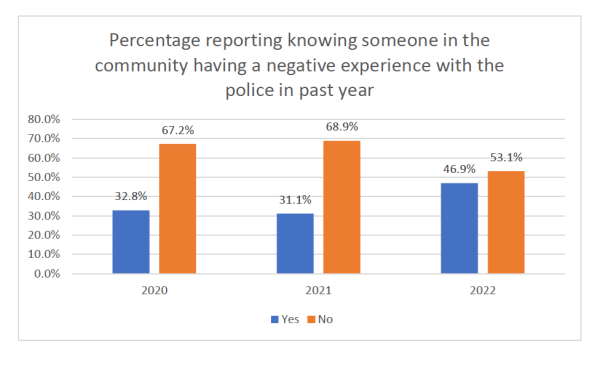

The percentage of residents having heard of someone in their local community who had had a negative encounter with the police was much larger than close personal experiences. Indeed, this past year nearly half of respondents (47%) reported knowing someone in the community who had a significant negative experience with the police in the past year. This is significantly more than the prior two years, when about 33% and 31% reported such knowledge. Knowledge of serious negative encounters with the police is higher than close personal encounters, at least in part,because there are so many ways of hearing about unpleasant incidences – e.g., from family, friends or media sources.

Consistent with past surveys and a considerable body of empirical literature, we again found statistically significant and relatively strong differences in negative encounters with the police by race and ethnicity. In 2021, African American respondents were more than twice as likely (29%) than white respondents (13%) to report that they or someone close to them had a negative experience with the police. At nearly 17%, persons responding that they weresome other race or ethnicity were only slightly more likely than whites to report this type of experience and much less likely than African Americans.

Well over half of African American respondents (59%) knew someone in the community who had a serious negative interaction with the police – this is 20 percentage points higher than whites and about 10 percentage points more than those identifying as some other racial group. African Americans were clearly at heightened risk of experiencing anegative encounter with the police than either white respondents or those of some other racial/ethnic status.

In general, there appears to be an increase in negative experiences with the police. This is particularly clear when wefocus on hearing of negative encounters by others in the community. From last year, white respondents’ hearing ofsomeone else in the community having a negative experience rose from 23% to 39%, African American’s reporting of hearing of someone in the community rose from 48% to 59%, and those responding as other (i.e., nonwhite, non-African American) increased from 20% to 48%. It is unfortunate that the composition of the “other” category is so diverse that it is difficult to tease out the specific groups that are experiencing increased knowledge about serious encounters with the police.

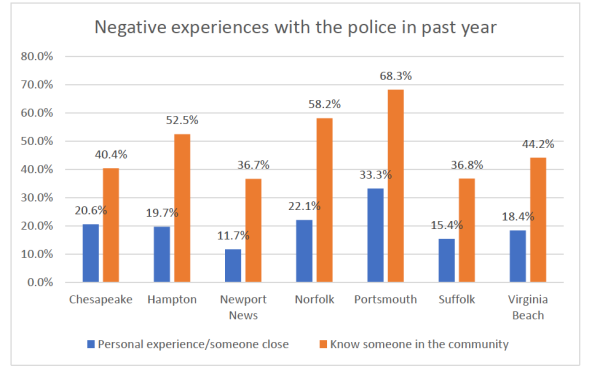

While the variation in personal negative experiences with the police (and/or experiences of someone close) appears to vary across cities ranging from 12% (Newport News) to 33% (Portsmouth) – the relationship is not statistically significant and may well have resulted from sampling variation. It is also important to note that the total sample size is lower than most previous years, reducing statistical power to detect small but potentially important differences. Further, although these analyses focus on Hampton Roads as a whole, sample sizes for the individual cities vary considerably and even with the appropriate weighting, we encourage caution with making comparisons between cities with relatively small sample sizes.

Knowledge of someone else’s negative experiences with the police in the community, in turn, does significantly varyby city. Knowledge of negative encounters with the police in Suffolk and Newport News were relatively low (both 37%) while Chesapeake and Virginia Beach were slightly higher but still under half of respondents (40% and 44%, respectively). Hampton (53%), Norfolk (58%) and Portsmouth (68%) all have a majority reporting that they knew someone in the community who had serious negative experiences with the police.

Satisfaction With and Trust in the Police

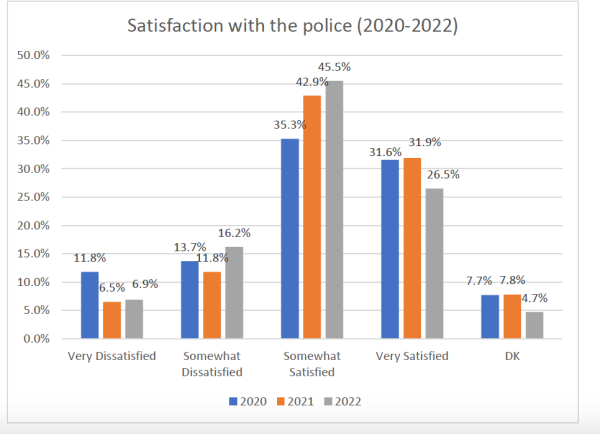

Hampton Roads residents were asked two questions focused on satisfaction with and trust in the police. These questionswere also asked in 2020 and 2021. Over time just under one-third of the sample responded that they were very satisfied with the police, and there appears to be recent decline in being very satisfied, from 32% in 2020 and 2021 to 27% in the most recent survey.

While these number may appear relatively low, when we look at the percent somewhat satisfied, we add another 35-45%(over time) to the generally satisfied group. Thus, in 2022, fully 72% of respondents reported that they are somewhat or very satisfied with the police. This is relatively consistent over the past few years.

There is also a fairly solid general trust with the police in Hampton Roads. Over the past three years, consistently a third or more of respondents (34%-39%) reported that they had a great deal of trust in the police. Another significant proportion (38%-44% reported that they were somewhat trusting of the police. Combining these figures, we see that fully 77% were at least somewhat trusting of the police. Similar to satisfaction, it does appear that fewer people are reporting a great deal of trust (39% in 2021 compared to 34% in 2022) with a slight increase in those reporting being somewhat trusting of the police (from 41% to 44%).

Satisfaction and Trust in the Police by Race and Ethnicity

The Life in Hampton Roads survey data show that persons of color are more likely to experience serious negative encounters with the police than are whites. Past findings from the survey and empirical research nationwide support the hypotheses that persons of color are also less satisfied with and trusting of the police than are whites.

Results from the 2022 survey continue to show significant racial and ethnic disparities in satisfaction with the police. White respondents are more than twice as likely as African Americans to respond that they are very satisfied with the police, and about17 percentage points more likely than those identifying as other races. While a considerable number of African Americans and those characterized as other report being somewhat satisfied with the police, summing those two categories still shows whiterespondents (83%) being more satisfied with the police than African Americans (67.1%) or others (70.2%).

The story is largely replicated when we focus on trust in the police. Nearly half (48%) of whites say they have a great deal of trust in the police versus only 14% of African Americans and 31% of those responding as other races. The vastmajority of white respondents (87%) trust the police somewhat or a great deal, while far fewer African Americans (70%) or those characterized as other (56%) hold such trust. Alternatively, twice as many African American (10%) and other races (11.5%) report that they have no trust at all in the police compared to whites (4.5%).

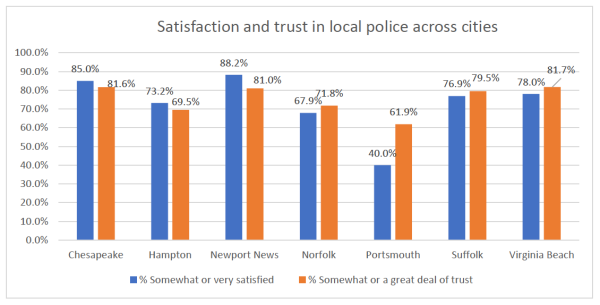

Perceptions of the Police Vary by City

Both satisfaction and trust in the police varied significantly by city. More than three-quarters of respondents in Newport News (88%), Chesapeake (85%), Virginia Beach (78%) and Suffolk (77%) reported being very or somewhat satisfied. Fewer than three-quarters of respondents in Hampton (73%) and Norfolk (68%) reported satisfaction with police, with lowest satisfaction rate in Portsmouth (40%). The trends were similar for trust with Chesapeake, Newport News, Virginia Beach and Suffolk all reporting between 80%-82%, while Hampton (70%) Norfolk (72%) and Portsmouth (62%) all have ratings 10 to 20 percentage points lower.

Willingness to Call the Police

Another way to estimate public attitudes toward police is to assess their willingness to utilize their services. We asked survey respondents how likely they would be to call the police if they saw someone:

- Breaking into a home or building

- Assaulting someone

- Selling drugs

Close-ended response categories were very unlikely, unlikely, neither likely nor unlikely, likely, or very likely. In general, we found that respondents were willing to call the police, especially in cases where someone was breaking into a home or building or if they witnessed someone assaulting another. Nearly three-quarters of the sample responded that they would be very likely to call the police in these two situations. Another 20%-21%, totaling 94%-95%, reported that they would be likely to call the police. The likelihood changes when we focus on witnessing someone selling drugs. A far smaller proportion of the sample reported they would be very likely (43%) or likely to call the police (21%), and 36% reported that they would be unlikely to call the police.

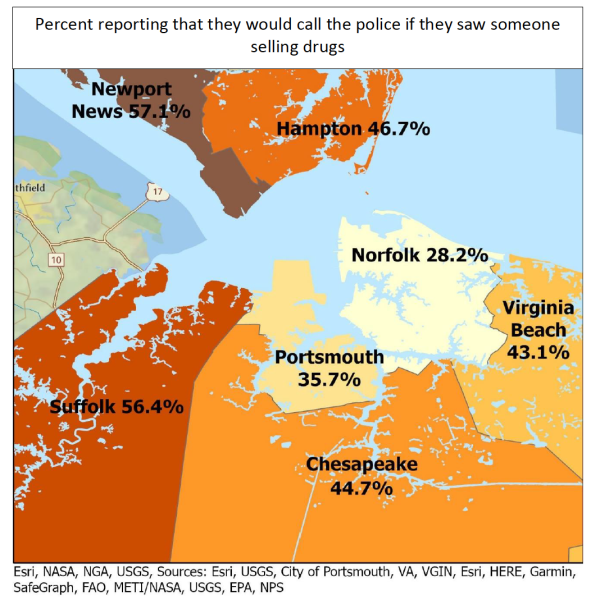

To explore this data further, we dichotomized the three variables to distinguish those who were very likely to report an offense to the police versus those less willing (e.g., very unlikely, unlikely, neither likely nor unlikely, and likely). The first two variables (breaking in and assault) did not significantly vary by cities across Hampton Roads. However, willingness to report witnessing someone selling drugs did vary significantly across cities. More than half of the respondents in Newport News (57%) and Suffolk (56%) would be very likely to call police if they saw someone selling drugs. Chesapeake, Hampton and Virginia Beach all had between 43% and 47% of respondents indicating that they would call the police if they saw someone selling drugs. Finally, 36% of respondents from Portsmouth and 28% of respondents from Norfolk reported that they would call the police in a situation involving drug dealing.

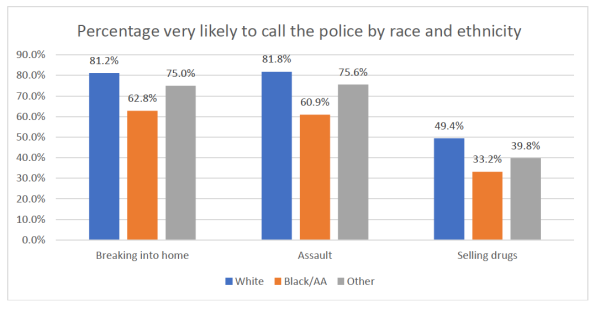

Using the same dichotomization (very likely versus all other categories) we examined respondents’ willingness to call the police in the three situations described earlier by race. Here we find relatively strong and statistically significant differences. The vast majority of white respondents (81%-82%) responded that they would call the police in cases of someone breaking into a home or building or seeing a person being assaulted while a much lower percentage of African American respondents indicated the same (63% and 61%, respectively). Respondents of other race/ethnicities are also less likely than white respondents to call the police in cases of breaking/entering and assault (75% and 76%, respectively). In the third situation, witnessing the selling of drugs, white respondents are much less likely to be willing to call the police (49%) than in the other situations, but so are African Americans (33%) and those of other races (40%). These results suggest relatively strong differences between racial groups.

While a full multivariate analysis of these findings is beyond the scope of this preliminary press release, the data show shown that African American respondents have more negative experiences with the police and are less satisfied and trusting of the police. Bivariate statistical analyses suggest willingness to call the police in each of these situations is correlated with both negative experiences with the police as well as trust and satisfaction with the police. Importantly, we find that while negative experiences and satisfaction with the police are significantly correlated with willingness to call the police, trust in the police is the strongest factor affecting willingness to call. Those who trust the police (somewhat or a great deal) are about 25 percentage points more likely to report being willing to call the police if witnessing a break-in or an assault than those having less trust in the police. Further, while respondents were less likely to report being willing to call the police when witnessing someone selling drugs, those who report great trust in the police were about 27 percentage points more likely than those less trusting to call the police.

The Life in Hampton Roads Data report and press releases will be placed on the Social Science Research Center websiteas they are released (http://www.odu.edu/al/centers/ssrc). Follow-up questions about the 2022 Life in Hampton Roads survey should be addressed to:

Tancy Vandecar-Burdin, PhD

Director, The Social Science Research Center Old Dominion University

757-683-3802 (office) tvandeca@odu.edu